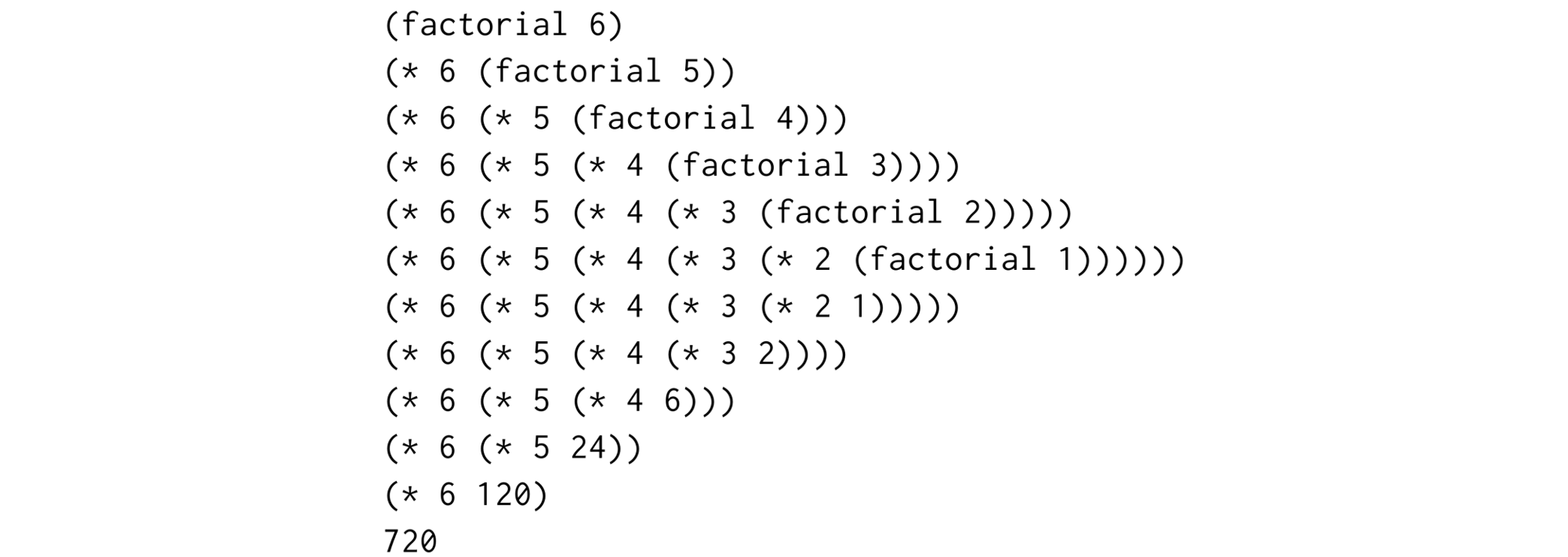

A diagram from Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs showing how to decompose a function call into all its separate steps.

In a technical interview, it’s common to not have a way to run the code you’ve written. A whiteboard interview is such a case, but I’ve also seen plenty of interviews where you write code online, but never run it.

It’s good to think through a problem without running it. After all, you want to catch bugs before they get to production! But let’s be honest: we catch many of our smaller bugs with the help of a compiler or runtime. Type errors, unit tests, even manual testing are all common ways to iterate on your code.

So what do you do on the whiteboard or in a collaborative text editor?

Run the code, not the algorithm

Hopefully, your interviewer doesn’t care about syntax errors, and substantial logic errors are easy to find. The problem I’ve seen is with errors like off-by-one errors in loops, or doing mutations in the wrong order. These types of bugs don’t cause problems in small test cases, so the best thing to do is be methodical with your testing.

Take the following implementation of a Depth-First Search (DFS). Can you spot what’s wrong? (As an aside, spotting bugs is a skill effective interviewers need to develop.)

def dfs(root):

stack = [root]

while stack:

node = stack[-1]

if is_desired_node(node):

return node

for child in node.children():

stack.push(child)

return None

I’ve seen candidates make mistakes like this, and I personally wouldn’t penalize them for it. But then, if I asked them to run through the code, they also had trouble finding the bug, because they ultimately ran through an idealized mental model of a DFS, not their actual code.

The first step is to make sure you’re paying attention to your implementation.

Write down the relevant state

Whatever your algorithm, there is some state that evolves over time. In the DFS example, that state is the stack, the current node and even the current child being iterated over in the nested loop. Even with recursive algorithms, each invocation of the function has parameters that you want to track over time.

Figure out what your state is, and write it down in a structured way. What I like to do is create a table with different pieces of data and create a new row every time there’s a mutation or a new recursive function call. Assuming a tree structure like:

1

/ \

2 3

/

4

The state would evolve like this:

| stack | node | child |

|---|---|---|

[1] |

None |

None |

[1] |

1 |

None |

[1] |

1 |

2 |

[1 2] |

1 |

2 |

[1 2] |

1 |

3 |

[1 2 3] |

1 |

3 |

[1 2 3] |

3 |

None |

And so on…

(Now can you see the bug?)

It’s okay to update the state in place instead of creating a table, but just do so in the same order: one piece of state update at a time. Which leads us to…

Go line by line

I’ve seen candidates treat a block of their code as a black box, updating multiple parts of their state in one step. The bug is often hiding in that block of code, and it would be easy to discover if the candidate had actually executed individual lines.

For example, the candidate might evolve the state as follows:

| stack | node |

|---|---|

[1] |

None |

[1] |

1 |

[2 3] |

1 |

This goes back to running an idealized model of the algorithm. The candidate knew the algorithm removed an element from the stack, then pushed the children onto the stack. To save time, the candidate then combined these two steps without thinking how each line of code affects (or in this case fails to affect) the state.

Instead, only update your state with the effect of one line of code at a time.

To find small bugs without actually running your code, you have to be methodical:

-

Simulate running the actual code, not the underlying algorithm in your head.

-

Write down the relevant state and update it over time.

-

Only update the state according to the effects of a single line of code at a time.

With these principles in mind, you’re more likely to find mistakes in your own code, while demonstrating your attention to detail and your ability to debug buggy code.