Today’s article is geared toward candidates looking to improve their algorithm skills for interviews. As usual, while I don’t believe interviews should require preparation for experienced candidates, the reality is it helps to prepare.

A common type of question I see in interviews is the “iterator problem”. In Java, there’s an Iterator type that allows iterating through some collection of values using two methods:

hasNext()- returnstrueif the iterator has any more values to producegetNext()- if there are more values to produce, returns the next value and internally updates the iterator’s state to move to the next value

This type is used used for “for each” loops in Java, of the form for (Object value : iterable). That makes iterators very useful in Java, as they allow you to go through a collection of values without necessarily loading all the values into memory at once.

In the interview setting, an iterator problem is designed to get you to think about how a typical recursive or iterative algorithm proceeds, then explicitly store and update the required state in order to pause and resume the iteration in the middle. Some examples of iterator problems are to implement an iterator that:

- Given a set of values, produces all possible subsets of the input set.

- Given k lists, produces elements from each of the lists, interleaving values from each of the lists in order.

- Given a tree, produces all the leaf node values in “left-to-right” order. Equivalently, flatten a deeply nested list of values.

In today’s article, I’m going to deep dive into the last one, in order to show a general technique useful for converting recursive algorithms into iterators.

Flattening iterator

Let’s start by understanding the problem. You have a NestedList structure that contains either:

- A terminal (leaf) node with a single value.

- Or a non-terminal node with children, each of which is a

NestedList.

You can distinguish the two by checking the value of node.is_terminal. For completeness, we can represent a NestedList in Python as follows. I’ve added some factory methods to help construct both terminal and non-terminal nodes.

class NestedList:

"""

A node in a tree that is either:

- A terminal (leaf) node with a single value.

- Or a non-terminal node with children, each of which is a `NestedList`

"""

@classmethod

def terminal(cls, value):

return cls(value, None)

@classmethod

def nested(cls, *children):

return cls(None, children)

def __init__(self, value, children):

assert value is None or children is None

self.is_terminal = children is None

self.value = value

self.children = children

(We’ll assume if a NestedList has a children list, it has at least one child.)

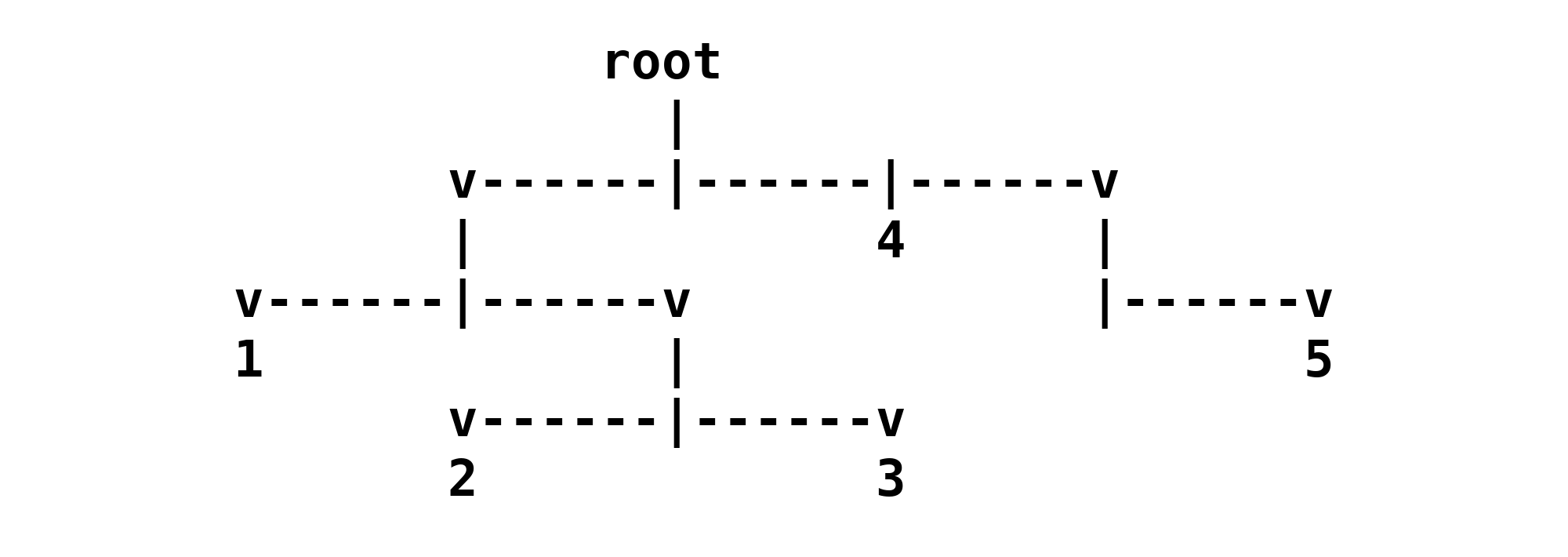

To make our problem more concrete, let’s define an example NestedList, which the following comment also describes with two different visual representations. Given that the children of each node are ordered, there is an overall order to all the terminal values, namely 1, 2, 3, 4, 5.

# A sample `NestedList` that can be used as inputs to the traversal algorithms.

#

# root

# |

# v----|--|---v

# | 4 |

# v--|--v |--v

# 1 | 5

# v--|--v

# 2 3

#

# [[1, [2, 3]], 4, [5]]

NESTED_LIST = NestedList.nested(

NestedList.nested(

NestedList.terminal(1),

NestedList.nested(

NestedList.terminal(2),

NestedList.terminal(3)

)

),

NestedList.terminal(4),

NestedList.nested(

NestedList.terminal(5)

)

)

We’ll use this definition to define our problem: implement an iterator that, given a NestedList, produces all terminal values within the list in order. So, given the above list, the iterator would produce 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 in that order.

(Note: even though the entire tree is loaded into memory with this definition, you can imagine an alternate definition where the children are loaded on demand. That makes the need for an iterator more apparent.)

Solving the problem recursively

To make solving this problem easier, let’s start with a more common problem: define a function that returns a flattened list of terminal values, in order. This will necessarily create an in-memory list with all the terminal values, but it illustrates the basic algorithm.

I won’t go into the algorithm in much detail, because it’s a straightforward recursive depth-first search. But, here’s the algorithm for reference.

def recursive_in_order(nested):

"""

Return a list of all the terminal values, in order, using recursion.

Demonstrates the most straightforward implementation.

"""

if nested.is_terminal:

return [nested.value]

# The following could be implemented as a list comprehension in Python, but

# I'm showing the algorithm as nested loops to explicitly show what

# intermediate state is required for this algorithm.

result = []

for child in nested.children:

for value in recursive_in_order(child):

result.append(value)

return result

I could have written the code more elegantly in Python, but I chose to use for loops to make the implicit state more explicit. There are two pieces of state that are being stored and updated, in the recursive case:

- The loop index for which child is being processed (the first for loop).

- The loop index for which element in the result of the recursive call is being processed (the second for loop).

We’ll see shortly how these pieces of state are explicitly stored and updated in our iterator.

Storing and updating explicit state

We can now convert this recursive algorithm into an iterator. But first, let’s define a skeleton iterator to see what we’re implementing. In Python, we could have used generators (namely the yield keyword), but typically, we want to implement a Java-style iterator. So let’s define a class that can be initialized with a NestedList, and has the has_next and get_next methods:

class NestedListIterator:

"""

A Java-style "iterator", which consists of two methods:

- `has_next` - whether there are more values that can be produced

- `get_next` - produce the next value, if there is any

The goal of this class is to store the iteration state, basically the same

state that's present in the recursive algorithm but explicitly stored and

updated in order to allow the iteration to pause and resume.

"""

def __init__(self, nested):

pass # TODO

def has_next(self):

pass # TODO

def get_next(self):

pass # TODO

We’ll start by implementing the constructor, which is where we set up our state. As a reminder, the two pieces of state we need to store and update are:

- The index of iteration over the children. We’ll call this

i. - The index of iteration over the result of the recursive call. We’ll represent the recursive call itself with a child

NestedListIteratorinstance, and the index of iteration over its values will be implicitly stored inside that child iterator.

As a base case, if the current NestedList is a terminal value, we don’t need the child iterator. However, we do need to know if we’ve already produced the terminal value, for which we’ll reuse i. Putting all this together gets us two pieces of initialization in the constructor:

def __init__(self, nested):

self.nested = nested

self.i = 0

self.child_iterator = \

None if nested.is_terminal \

else NestedListIterator(nested.children[self.i])

Checking if there’s another value to produce has two parts:

- The base case for terminal values, where we check if we’ve already produced the terminal value.

- The recursive case where we check the child iterator. Here, we’ll make the assumption that the child iterator is always set up to produce the next value. Certainly in the constructor we set up the child iterator that way.

def has_next(self):

# Base case

if self.nested.is_terminal:

return self.i == 0

# Recursive case

return self.child_iterator and self.child_iterator.has_next()

Finally, the get_next method also has the same two cases:

- The base case for terminal values.

- The recursive case where we use the child iterator.

In both cases, we have to update the stored state. For the base case, we just increment i to denote that we’ve already produced the terminal value.

The recursive case is a little more complicated. Think about this in the same way the two loops in the recursive solution proceed: if we’ve exhausted the result of the recursive call, go to the next child. That means incrementing i and setting up the next child iterator. Note that the index of iteration within the child iterator automatically increments when we call get_next on it!

def get_next(self):

# Base case

if self.nested.is_terminal:

assert self.i == 0

self.i += 1

return self.nested.value

# Recursive case

assert self.child_iterator

child = self.child_iterator.get_next()

if not self.child_iterator.has_next():

self.i += 1

self.child_iterator = \

NestedListIterator(self.nested.children[self.i]) \

if self.i < len(self.nested.children) \

else None

return child

Notice we set up the next child iterator when the current child iterator finishes. Doing so maintains the invariant that when the next call to has_next or get_next is made, the internal state is already pointing to the next value, if any.

What about a non-recursive solution?

As a side note, we could have implemented the iterative depth-first search algorithm using a queue, then translated that into an iterator. That certainly would be easier, but I wanted to talk specifically about how recursion plays into iterator problems. The reason this is important is because many of the iterator problems I’ve seen deal with iterators of iterators, making them a natural fit for recursion.

Interview problems are often about taking foundational concepts and presenting them in new ways. In the case of iterator problems, that means taking straightforward algorithms and spreading out the progress of the algorithm across multiple method calls. However, once you understand that the underlying approach is the same, and the iterator simply requires you to make explicit what was implicit before, the problem becomes tractable.

In the spirit of always having something to show at the end of an interview, it’s often good to start with the simplest version of the problem and build it into the required solution.